27 October 2020, 19:13 | Viktoryia Kavalchuk, TUT.BY

Maryia Shakuro is 29 years old. She is the Belarusian Rugby National Team and Minsk Hrazhdanachka team captain. On 11 October, the resident of Minsk was arrested during a peaceful rally and jailed for 10 days. Once released from police custody, Maryia told Viktoryia Kavalchuk, a SPORT.TUT. BY journalist, about the conditions in Akrestsina and Zhodzina, OMON riot police officers addressing her as unbelievable and cutie, allowable items in an inmate package, lectures on philosophy and feminism right in the cell, and her unwillingness to leave Belarus no matter what.

“It’s morally easier for me to do something than to keep silent and sacrifice my conscience”

“For a long time I’ve had my own opinion on the state policy in Belarus. In short, I strongly disapprove of it. But since this year’s elections took a new turn, the Belarusian opposition have been massively campaigning against the current government, and therefore, I have been expressing my political views more actively too.

“It’s hard to remember what exactly the last straw, the point of no return was. I believe it all started in March with Covid-19, which provoked a huge wave of resentment and indignation in people. Popular discontent was growing like an avalanche. Everything we are witnessing these days is just a predictable consequence of state policy.

“At first, I expressed my bitterness through reposting on social media. I wanted more of my friends, particularly those abroad, to know what is going on in Belarus. Of course, I realized that once I declared my disagreement publicly, I had to be ready for any consequences. I was fully aware of the total lawlessness my county was descending into, of brutal violations of all human rights.

“But this is just who I am. It’s morally easier for me to do something, even if it’s punishable, than to keep silent and sacrifice, compromise my conscience.

“I understood it all, but never feared. When you break a law, you are scared, haunted by guilt. But I was just walking around my city, so I had nothing to be afraid of.”

“I was standing under my umbrella watching the riot police dispersing the crowd. And then it was my turn”

“On Sunday, 11 October, I took a trolleybus to go to the rally. I saw people gathering in small groups and moving towards the Stele (Minsk Hero City Obelisk). Later a break-up began, and the people started running to the courtyards. There were police vans circulating the streets, but at first the arrests were few. The protesters were heading for the Karona shopping mall on Kalvaryiskaya street, so I joined them.

“On Kalvaryiskaya we converged with other columns of protesters in one big demonstration. As a rule, police do not make arrests in big crowds; they usually start grabbing protesters when a march is just beginning or closer to the end. It is much easier to snatch one or more individuals from a smaller group.

“From Kalvaryiskaya, the march headed for the Pushkinskaya metro station, but we didn’t manage to go far, since the same blue police vans and water cannon with orange paint were following.

“At the intersection of Kalvaryiskaya and Alsheuskaya streets, arrests began again. Some started running away, but I just stopped on the sidewalk as I didn’t want to be tripped up, beaten or harshly detained while running.

“I was standing under my umbrella watching the riot police dispersing the crowd. I didn’t feel guilty at all, and I understood I could now be either arrested too or just ignored. It was a fifty-fifty chance. But in the end the policemen approached me.”

“Balaclava-clad people were hooting at me, ‘Hey you, Unbelievable! Cutie!’”

“If compared to the August arrests, mine can be described as a very polite one.

“I was grabbed by an arm and dragged into a bus with soft seats intended for OMON riot police. There I was searched by some female officers, then transferred from one prisoner transport vehicle (PTV) to another, until a group was formed to be taken to a certain police station.

“While going from one PTV to another, I was accompanied by some balaclava-clad people who kept hooting at me, ‘Hey you, Unbelievable! Cutie!’ Of course, it was hard for me to keep my mouth shut and not shout something back to this injustice. But I managed to control myself.

“Instead, I was trying to find out with other law enforcement guys why I had been arrested in the first place. Obviously, to no purpose.

“When the PTVs were filled up to go to the police station, we were strongly suggested not to talk to each other, not to speak at all. However, some guys attempted to discuss human rights, laws and the Constitution with the OMON riot policemen, but the dialogue was pretty brief.”

“In the police van I had no fear, but I was shaking with fury”

“Even in the police van, I had no fear. The only feelings overwhelming me were fury and complete disdain. I was literally shaking with rage. But I wasn’t worrying about myself, I was more concerned about the people around me, I feared they might be insulted or beaten.

“In the van, we were a pretty motley bunch – young girls in their twenties, an adult woman of my mother’s age with her son. All the women were seated on the benches, and men made to kneel on the floor with their faces down, they were not allowed to raise their heads.

“The detainees were the men of all ages. One of them was drunk and was yelling he had been just getting back home from work. ‘Look, there is a lunchbox in my bag, working clothes, why am I arrested?’ Obviously, he was not the one who came to participate in the rally. Nevertheless, all of us were taken to the Partyzanskii police station and then I saw this man transferred to the prison in Zhodzina.”

“I couldn’t get warm in the detention center. We were given plastic slippers instead of our footwear”

“The scariest thing about being arrested is the uncertainty of your future. And then a series of standard procedures follows.

“At the police station we were video-recorded, interrogated, had our fingerprints taken and our possessions listed, and an official report was drawn up. I felt more or less all right. At the Partyzanskii police station the conditions were quite comfortable as we could sit on the bunks and talk. I know that in other police stations detainees were seated on the bare cement floor…

“I tried to get warm there since I got my feet wet during the rally. But I couldn’t. And then later in Akrestsina I couldn’t get warm either. The heating wasn’t on yet, and we were given plastic slippers with a cell number on them instead of our footwear.

“But I was well-prepared with my clothes as I went to the rally wearing thermal underwear, a fleece pullover and a windbreaker. The only thing I probably should have done differently was to put on some stretch pants rather than jeans.”

“I’m a vegetarian. My Akrestsina diet was cereals and bread”

“The first two nights I spent in Akrestsina. Can’t say I was shocked or anything when I saw my new bed in the cell. Perhaps, I was already prepared for it, so I just tried to make my stay there as comfortable as it could possibly be. (smiling).

“At first, sometime after midnight, I was taken to a cell on the third floor. Two women were already sleeping there. The lights were on, they are never off so that the prison guards can see what’s going on in the cell. I started making the bed when all of a sudden I was commanded, ‘Get out!’ to be taken to a cell downstairs.

“There in a five-bunk cell there were three women, all charged with some domestic crimes. In an hour or so another girl was brought. She was grabbed from a solidarity chain in Kamennaya Horka.

“Despite being stressed and in unusual conditions, I mean, I’m not used to sleeping in detention centers, I fell asleep quite quickly and slept tight all through the night. And the morning began with learning the ropes of the prison schedule.

“Wake-up is at 6 am. In 10 minutes or so it’s time for breakfast which is usually some cereal and tea. I was ok with morning meals, but had some troubles with lunch and dinner because I’m a vegetarian. As a rule, some chops or meatballs are served with a side dish, and a meat soup for a starter. So all I could eat was cereal and bread, luckily we had enough of both at the center.”

“When a witness was testifying, I couldn’t control myself and shouted, “These are all lies!”

“I was tried the very next day after my arrest. Of course, till the very end I was hoping to get a fine, but I was also ready to be jailed. Two of the three guys I was taken to the police station with were jailed for 15 days and the other one to 12. So, after their sentences I realized the chances to be just fined were ever so slim.

“My trial was online. But the witness was there, in Akrestsina, he was there, right next to me, not in a Zoom conference call window. So I spent quite a lot of time with him when waiting in the hallway, and then in the same office. I had enough time to study him, although he was wearing a medical face mask. I even looked him into the eyes.

“When he was testifying, I was standing right next to him wondering how anyone could be telling such a whopping downright lie to the court and me! I was burning with rage when he was testifying against 15 other detainees, not only me! It turned out he’d seen everyone, been everywhere! He said he’d seen people at the Pushkinskaya metro station, at the Stele, on Alsheuskaya street… And all of us had been chanting out the same slogans, we all had been clapping. Well, all his evidence on various cases were literally copy-pasted.

“It was utterly ridiculous to hear that I had been clapping since I’d carried my umbrella in one hand, so I couldn’t have clapped even if I’d wanted to!

“It was all resembling the absurd theater, so I couldn’t help but to shout out it was all just blatant lies. But the witness didn’t even care and just kept speaking. He was actually testifying under his real name. When released, I googled him and found out he was a district officer at the Partyzanskii police department.”

“Not even once did I cry when in jail. I knew it was exactly what they were trying to achieve”

“When my sentence was pronounced, my first thought was, ‘Phew! It’s just 10 days, not 15!’ (smiling)

“The only emotion I was overwhelmed with was rage. I was furious about the court procedures. So I was just sitting in that hallway trying to get a grip. But tears wouldn’t come. At all, not even once when in jail. I knew it was exactly what they were trying to achieve, so they were not going to see any of my emotional breakdowns.

“And then I just started thinking rationally on how to adjust, what to do, how to get used to these new conditions for the next ten days.

“The most difficult thing was to get used to sleeping with the lights on. In Akrestsina it was only a flashlight beaming down along the floor at the window. But in Zhodzina I was transferred to on the third day, the overhead ceiling lights were on all night long. We covered our eyes with face masks to fall asleep faster.

“Before the heating was switched on, it was also hard to get used to the constant, piercing cold because the window wouldn’t close tight. We asked the guards to do something about it, but in vain. So, when I could I slept covered with two blankets.

“Another discomfort was sleeping with a lot of clothes on. Like you are used to being able to touch the bed with your skin, and here you have to go to bed with clothes on, or otherwise you’ll freeze.

“And I’m not really used to waking up at six o’clock in the morning to the anthem of the Republic of Belarus (smiling). A pretty lousy entertainment, I should say.”

“My friends advised my boyfriend on what to include into an inmate package”

“I was lucky to get some packages. I arrived in Zhodzina on Tuesday, and by Wednesday I’d had some clothes. My boyfriend packed it. He had some ideas on what an inmate package should include, and he asked my friends for some advice on what I might need, from bras and deodorants, to comfortable pants and shaving sticks. He might have not figured it out for himself (smiling).

“You know, when you are free it’s hard even to imagine what things an inmate might ever need. And there are loads of things which are allowed and actually should be sent.

“We were lucky enough to ‘inherit’ from previous detainees some toiletries, like face wash, wet wipes. Because without it, it’s really hard to maintain good personal hygiene.

“When sending underwear to detained girls, make sure these are either sports tops or comfortable bras without any underwire. My boyfriend sent me an underwired one, so obviously, I was not allowed to get it, it just went to my personal belongings in the prison storage.

“Warm clothes can never be too much. Sleep masks, gloves and socks are never enough. If you don’t need them, some other girls will definitely be grateful to get them.”

“You have just a glass and a sliver of soap to wash your body in Akrestsina”

“During these long 10 days I got convinced that necessity is the mother of invention.

“For example, in our cell we had some colored pencils left behind by other women, but they needed sharpening. But how can you do it without a sharpener or a knife? But we found a way – you just rub them against the screw the window bar fastened with.

“In general, pens, pencils and paper were in high demand in the cell. What else could you do there but write or draw? I know our friends sent us some pens, but for some reason we got none…

“Speaking about personal hygiene, it was terrible in the Akrestsina detention center. I heard the conditions there are much worse than in Zhodzina.

“To wash in Akrestsina, we had to fill a glass or a bowl with water, take a soap bar, well, a sliver rather, left behind by someone else, and then proceed with ‘bathing’.

“In Zhodzina the situation was pretty much the same – in the cell we had to wash using bottles. But in the Zhodzina prison we were allowed to shower three times a week! I know it’s really a lot for politicals [political prisoners] who sometimes don’t get such a chance at all.”

“In the cell we would lecture on philosophy and feminism, and in the evening sing Kupalinka and Mury” [Belarusian songs associated with the protest movement]

“I was transferred from one cell to another, and at some point in Zhodzina I found myself in a cell together with other politicals. I imagine it happened just because the system is not really working properly.

“But thanks to this, I spent time in a wonderful company of smart people. Because of the girls, staying in prison had its perks benefiting both our hearts and bodies.

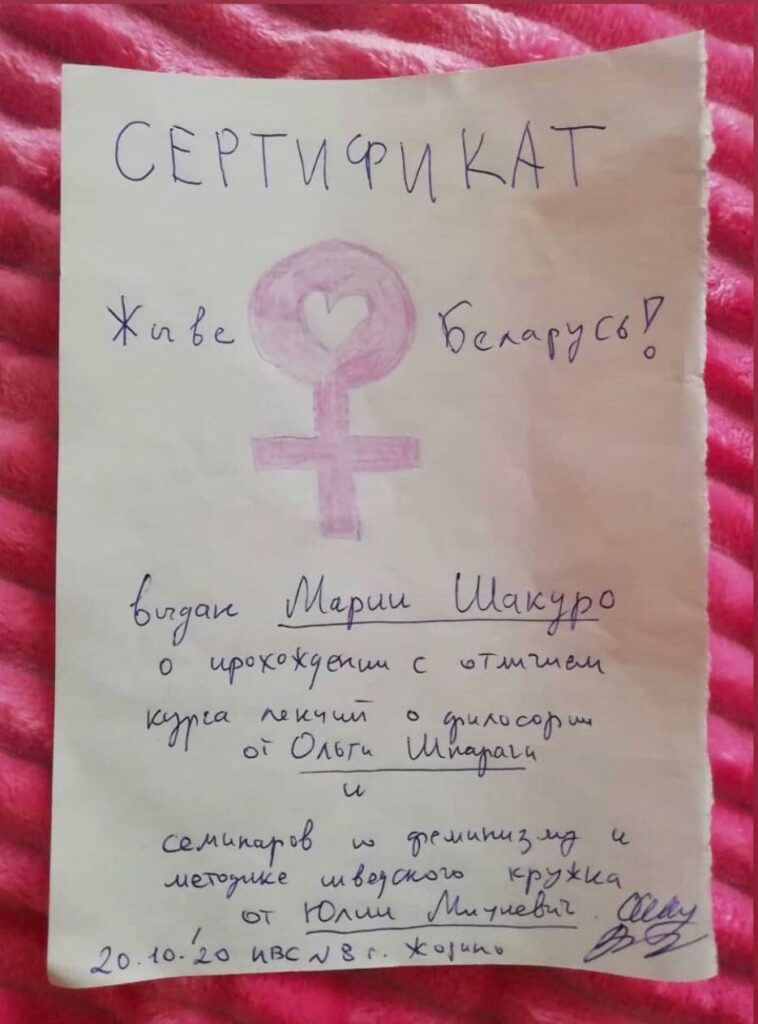

“We would start a day with morning exercises, then we’d have lectures on philosophy read by Volha Sparaha, a Coordination Council member and a Belarusian philosopher. She would pick various topics, from Michel Foucault to existentialism.

“After lunch, we had Yulia Mitskevich’s seminars. Yulia is a feminism movement activist. Also in our five-bunk cell there were other activists of the movement, Sveta Gatalskaya and a girl named Aryna who was also arrested for participating in a protest, although she and her friends were literally dragged out of their car.

Signatures. 20.10.2020, Detention center No. 8. Zhodzina.”

Source: TUT.BY

“Those lectures were not prohibited. Sometimes our prison guards played our ‘wonderful’ official radio station. It was so loud they couldn’t even hear each other, not mentioning us.

“In the evening we would sing with the girls. ‘Kupalinka’, ‘Mury’, ‘Belavezhskaya Pushcha’, ‘Try charapahy’. The guards were pretty relaxed about our singing, sometimes jokingly calling us a girls’ band.

“The favourite song of the official radio channel was ‘Lubimuyu ne otdaut’ [‘Do not give up on your beloved’ is a song created by Lukashenko’s supporters]. I was doing my best not to listen to it, so it wouldn’t start playing in my head like an earworm. I’m trying to forget it, it’s a horrendous nightmare of a song!” (laughing).

“My arrest convinced me this regime only makes people get united!”

“Aryna was the first to be released; in two days it was me. Volha Sparaha was free a couple of days later. On Sunday I was told that, once she was released, she was sentenced to 12 days more. I know Volha and her husband made a decision to leave Belarus.

“As for me, I have never wanted to leave the country. Here is my home, my friends, my team… But I do understand clearly that if my loved ones, my family, and me are directly threatened, it might be just wise to go abroad for a while. But at the moment, I’m not even considering it as an option.

“As the saying goes, you are not a true Belarusian, if you’ve never been jailed. And during those 10 days I figured out for myself the exact meaning of it. I survived my arrest and imprisonment without too much trouble, because I knew that many had been there before and many are likely to be jailed again. As we see every single day, this deepest Kafkian abyss yet is a bottomless chasm.

“But most importantly, after the arrest I realized how tightly the system and the president unite people. All their steps to prevent protests are actually backfiring. Soon there will be no one left untouched by the protests. It just unites people. And nothing can be done to stop it.”

“The system which neglects human rights so blatantly must not exist”

“After the arrest my opinion hasn’t changed, not even a bit. On the contrary, I think everyone who gets behind the bars, is reassured they are heading in the right direction. The system which neglects human rights so blatantly must not exist.

“I’ve been out free for a bit more than a week. I spent my first free days checking social media and answering my messages. I didn’t expect I would get so much care and support. And it took me some time to get used to the thought of how many nice people are there and how truly they were worried about me!

“I caught up on sleep a bit, rested, ran some family errands on the weekend. And back to work on Monday! I do painting jobs at a furniture factory.

“When in jail, we were talking with the girls about our food cravings, about what we were going to do first thing when out. ‘I’ll eat that pizza, or I’ll eat this sandwich.’ And then you are out and you realize your stomach got shrunk during those 10 days. Just a bite of a marshmallow makes you full. The air of freedom is more than enough!” (smiling).